Building a Scalable E-Commerce Data Model

If selling products online is a core part of your business, then you need to build an e-commerce data model that’s scalable, flexible, and fast. Most off-the-shelf providers like Shopify and BigCommerce are built for small stores selling a few million dollars in orders per month. Those e-commerce retailers working at scale must start to investigate a bespoke solution.

This article will look at what it takes to start building this infrastructure on your own. What are some of the areas to consider? What might the data model look like? How much work is involved?

Along the way, we’ll explore an alternative: API-based commerce platforms like fabric that manage data for you across products, pricing, and orders without locking you into a monolithic solution that slowly acquires technical debt and leads to replatforming.

Note: A full summary diagram of the e-commerce data model is at the end of the article.

[toc-embed headline=”Who Are Your Customers?”]

Who Are Your Customers?

First, you need to consider who will be purchasing items from your e-commerce application. How might you model customer information in a database as a result?

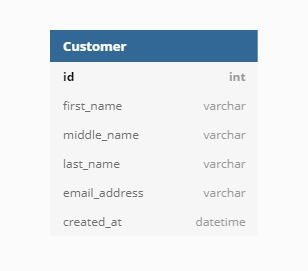

You’ll want to have basic information like your customer’s name and email address. Do you want your customers to be able to create a profile in your system or just fill out a form each time they want to purchase something? Just starting out, a basic model looks like this:

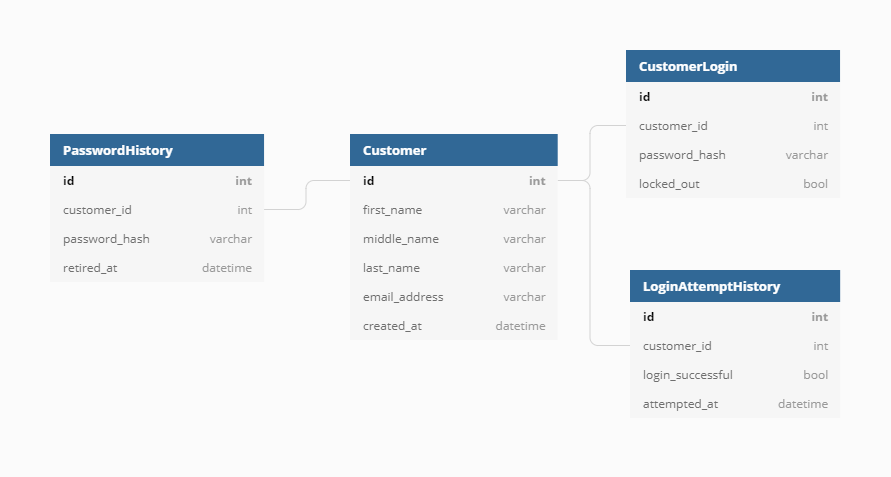

If you want your customers to have a persistent profile, then you need to build some way for them to log in to your application. Moving forward with more real-world requirements, you also want to keep track of their login attempt history and password history.

You also want to consider whether your customers are part of a large organization. If so, how would they like to handle password resets? Do they need single sign-on or OAuth support?

Addresses

Did you notice there’s no address tied to a customer in any of the data models shown so far? It might be your first inclination to include a customer’s address as part of those models. However, most customers will have multiple addresses and multiple kinds of addresses, like billing and shipping. B2B retailers might also have to consider multiple delivery locations based on the number of warehouses and offices they support.

What happens if the billing and shipping addresses are different? You’ll need to do more than just add extra columns to the Customer table. So how does storing a billing address affect the scalability of your application?

If you were to split the payment and shipping areas into separate (micro)services that each have its own database, then putting billing and payment addresses into the Customer area would lead to having “chatty” services.

To avoid this issue, you’re better off putting the addresses within the appropriate area/service that requires them. This, however, makes your data model becomes more complex.

One way to avoid much of this complexity is to consider an order management system (OMS). With this software, you can integrate the OMS into your data model without spending months of engineering time.

[toc-embed headline=”How Do You Organize Products And Catalog?”]

How Do You Organize Products And Catalog?

The first thing you see when you enter a store are products ready for you to purchase. The products are organized in a way that appeals to most customers. The same concept applies to an e-commerce web application, where you want to highlight the following:

- Best selling products

- Trending products

- New products

- The ability to browse products by search criteria

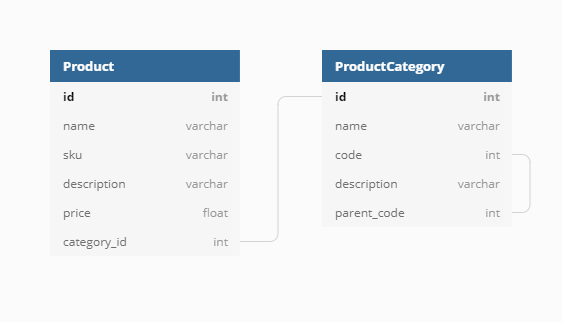

Providing customers with that information means you first need to keep track of a lot of data about your products, such as their prices and historical purchase data. Let’s see what a “first shot” at creating a data model for a product catalog might look like:

Here’s a Product table with some basic information, like a product’s name, SKU, and price. The product is also linked to another table representing various categories it’s associated with. You might also strategically add indexes and full-text search to the Product table to enable site visitors to efficiently search for various products.

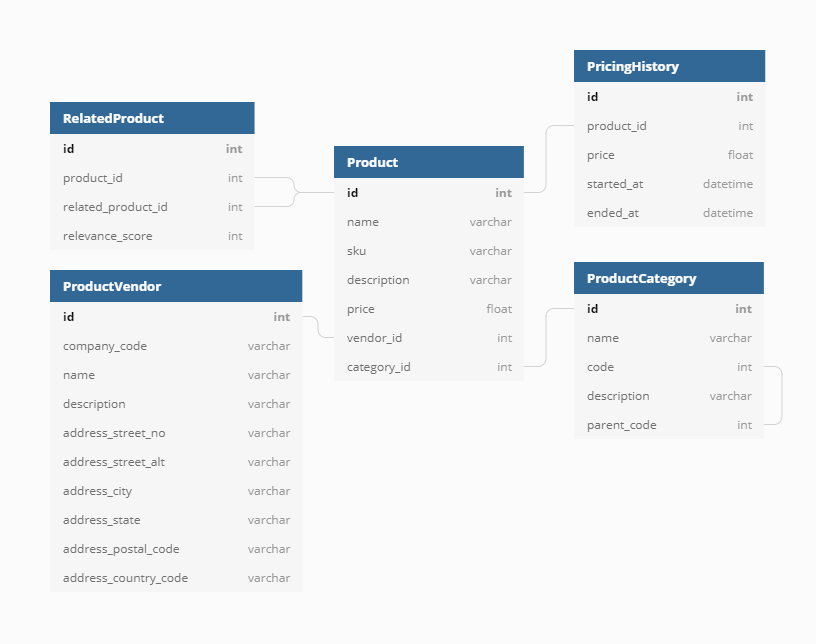

This is a decent first attempt. However, to get an even more realistic and useful e-commerce product catalog, you’ll need to support more requirements such as:

- Tracking pricing history so site administrators can analyze trends in product pricing

- Supporting related products to display on a product’s page

- Incorporating product vendors so customers can view all products sold by an individual vendor/company

To address those extra requirements, you might end up with the below data model. This model still isn’t perfect as it embeds your prices into the product itself, but at least it lets you maintain a previous pricing history.

Another option is to integrate your e-commerce store with a pricing and promotions engine that handles pricing for you. This will let you roll out different prices to different users based on their intent, location, cart, or order history.

Pricing

While the more complex product data model still has a product’s price in the same table, this may not be the best thing to do in a real large-scale application. For example, your organization has various departments, such as inventory/warehousing, sales, marketing, and customer support. You might have dedicated systems that allow merchandisers to change the price of an item since they are the experts in determining how much a product should sell for.

Similar to the considerations with a customer’s billing and shipping addresses, this would lead to cross-boundary/service communication if we left the price in the core Product table. Therefore, you want to store product prices under the data stores that the sales department owns. There are many different kinds of “prices” that haven’t been taken into consideration, including:

- Price (cost) when purchasing stock from vendors

- Customer sale price

- Discounted sale prices

- Manufacturer’s suggested retail price

Handling all these in the context of your organizational structure would require even more exploration and complexity in your data model. While your engineering team could accomplish this task, it’s going to take time. Using ready-made solutions can shave weeks or months off your e-commerce data modeling timeline.

[toc-embed headline=”How Do You Streamline Orders?”]

How Do You Streamline Orders?

Now that you have customers in your database and products available to purchase, you’ll need to think about how to design the order-taking process and data model. The process of placing an order looks something like this:

- A customer places products into their cart while browsing.

- The customer decides they want to purchase the products that are in their cart.

- They proceed to purchase the order.

- The customer gets an emailed receipt or confirmation number.

However, it’s rarely so simple. Placing orders is tricky as there are many moving parts:

- Products

- An active cart

- Cart converted into an order

- A finalized order with confirmation

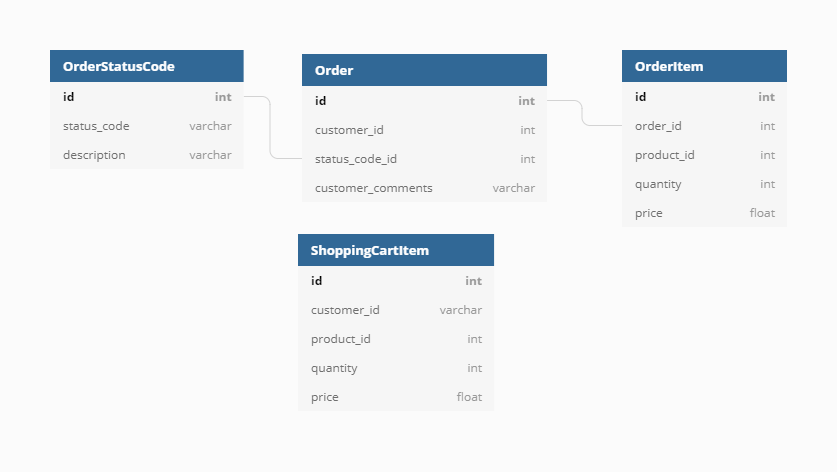

If you were to look at a simple data model for order placement, it looks something like this:

Notice that each row in the ShoppingCartItem table contains the “captured” price of the product. When the customer puts an item into their shopping cart should the price at that moment be “locked-in”? If so, for how long?

Note: How the price functions is a business requirement that would need to be discussed with your product owners, and so on, as mentioned in the “Pricing” section earlier.

The same question applies to an unpaid order. If a customer has ordered a discounted item, should they be able to keep the promise of that discounted price forever until they pay? Or does it expire? Other questions to consider for an orders data model include:

- Are you tracking analytics on orders?

- What happens if a customer returns a defective item?

- Should you handle shipping within the same data model or have a dedicated shipping context/schema?

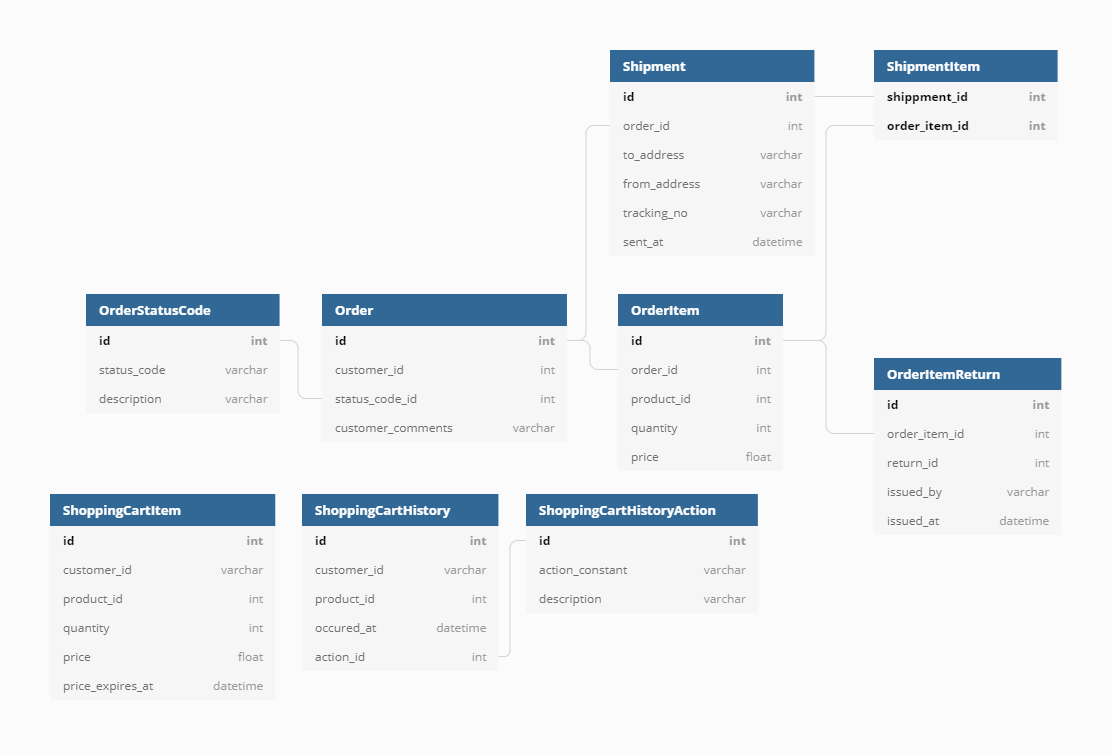

With some of these concerns in mind, you might end up with a data model that looks more like this:

Some things to take note of in this more complex orders model:

ShoppingCartItemnow supports an expiration date for a locked-in price.ShoppingCartHistorytracks when items are added or removed.- An order item may be returned (this still does not handle cases where 1 out of X items of the same product are returned).

- An order may have multiple shipments (e.g., how Amazon will sometimes split an order up into multiple packages/shipments).

[toc-embed headline=”Conclusion”]

Conclusion

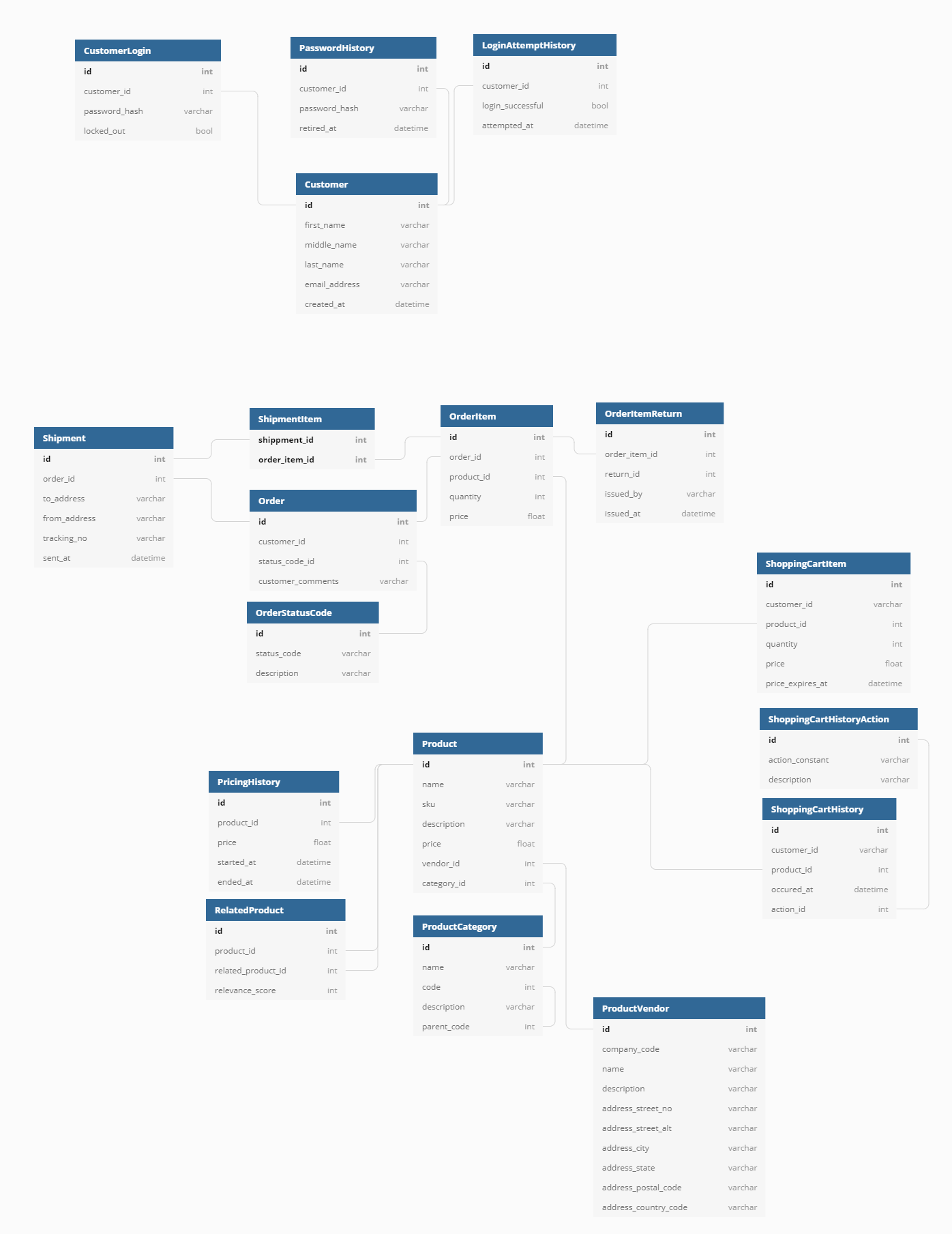

To help you see how all the pieces fit together, here are all the diagrams together. I’ve removed a number of links/lines to the Customer table to increase readability:

This article still doesn’t even cover many of the basics like payment processing and invoicing. Beyond the features covered here, you might eventually require more advanced features like:

- Coupon codes

- Taxes

- Third-party integrations with OAuth providers, other retailers, or partners

- Shipment tracking notifications

Building a data model for an e-commerce application, as you can see, is not so simple. What looks upfront to be a straightforward set of database tables is not so simple once you dig into real-world requirements.

There’s Another Way

What if you could have more of these abilities out-of-the-box? fabric is an all-in-one commerce platform that helps you do everything this article talked about, like manage customers, orders, and shipments. Most importantly, it is a microservices-based and API-first platform (i.e. headless). This means you can choose the services you need and integrate them seamlessly with any other internal or external service.

Tech advocate and writer @ fabric. Author of Refactoring TypeScript and the creator of Coravel.