The Truth About Third-Party Marketplaces and The Fallacy of The Long Tail

This article was originally published on LinkedIn.

marketplace

noun

- An open space where a market is or was formerly held in town.

- The arena of competitive or commercial dealings; the world of trade.

With the breathtaking pace of innovation in e-commerce, it is far too easy to get swept up in a perpetual whirlwind of trends and fads and the occasional overblown hype cycle.

Case in point: creating and hosting a third-party marketplace has become an increasingly trendy way for enterprise brands to scale their long tail product assortments quickly and cheaply—even though incremental revenues are unlikely to materialize from offering infinite “endless aisles” to customers.

For example, Albertsons launched its third-party marketplace in 2018 with 40,000 products and promised to stock an “infinite aisle” of 100,000 products by the end of the year.

It quietly shut down the whole operation just two years later:

[Source]

The initiative failed because the grocer tried to offer a “hodgepodge” of products instead of a highly-curated selection. Albertsons learned an expensive lesson that offering an “infinite aisle” of goods was not the goldmine it was thought to be.

But Albertsons isn’t the only one that has run into trouble. Best Buy also closed its U.S. marketplace back in 2016 after 4 ½ years of dismal sales. The company had promised it would add one-third more products to its offerings, but total third-party marketplace sales only contributed to less than 1% of the company’s total revenue.

When they mercifully pulled the plug, Best Buy’s spokesperson said there were two reasons:

“To invest the money the company is spending on supporting the marketplace business into other areas of strategic growth, and customer confusion over marketplace purchases.”

Meanwhile, the “big mess” at Barnes & Noble was partly why the bookseller closed its third-party marketplace in 2020. The book industry is particularly sensitive because roughly 98% of the books that publishers release sell fewer than 5,000 copies. In fact, of the 58,000 trade titles published per year, a shocking half of those titles “sell fewer than one dozen books.”

Staples had to confront similar challenges during my time there as CDO and CTO. We wanted to provide our B2B customers with “every product their business needs”, and at one point, we considered exploring a third-party marketplace.

However, a significant amount of revenue was generated via Staples’ in-store digital kiosks, and there was no way we would risk a suboptimal customer experience with a fully third-party run platform.

Ultimately, my team decided on curation over “infinite aisles” with the launch of Staples Exchange, which was our custom-built platform for B2B vendors. Staples Exchange was used to power our customer-facing Staples Marketplace dropship program, which significantly boosted revenues with (~2x) larger basket sizes and (2.5x) more omnichannel customer engagement.

[toc-embed headline=”The Fallacy of The Long Tail”]

The Fallacy of The Long Tail

“I would like to tell you that the internet has created such a level playing field that the Long Tail is absolutely the place to be—that there’s so much differentiation, there’s so much diversity, so many new voices. Unfortunately, it’s not. […]

Although the tail is very interesting, the vast majority of revenue remains in the head. And this is a lesson that businesses have to learn. While you can have a Long Tail strategy, you better have a head, because that’s where all the revenue is.”

Eric Schmidt, Former CEO of Google

Enamored with the success of Amazon, many online retailers have willingly (and enthusiastically) ceded control of customer experience, pricing, and brand image to third-party sellers. Their hope is to build a vibrant marketplace that can mimic the form and function of what is arguably the greatest e-commerce business in the world.

Today, third-party marketplaces are being promoted as the ultimate way of capturing lucrative sales deep in the long tail. The argument is that “endless aisles” fuel the marketplace model’s profitability, which is why Amazon’s third-party marketplace sales continue to soar.

But Albertsons, Best Buy, and Barnes & Noble all played the long tail game and failed to gain any meaningful traction.

Does this mean the economics of third-party marketplaces and “infinite aisles” are really not as promising as they’re claimed to be?

The Long Tail Theory

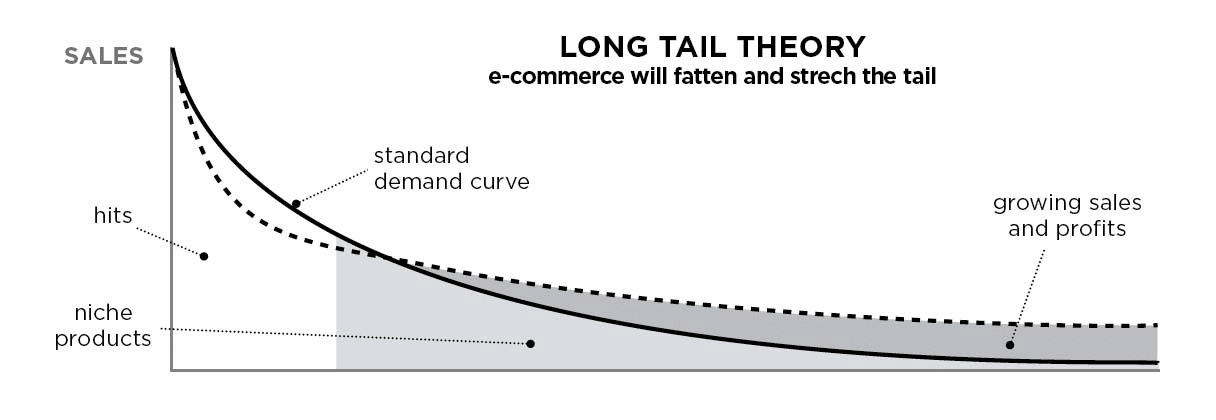

Chris Anderson, the former editor-in-chief of Wired magazine, made a big splash in 2004 when he published an article called The Long Tail. The idea was that the internet gave online retail outlets infinite shelf space, which meant that they could carry an unlimited assortment of products and attract more demand.

He predicted that online retailers would make increasingly more profit selling small quantities of many niche products versus the old model of making the bulk of their profit selling a concentrated number of popular products.

In other words, the “tail” of the sales distribution curve would become longer, fatter, and more profitable while the “head” would shrink and become less profitable. Below is an illustration of his theory:

[Source]

[toc-embed headline=”A Healthy Dose of Reality”]

A Healthy Dose of Reality

Alas, although Anderson’s theories and predictions were met with much fanfare and media attention, they didn’t pan out in the real world.

The Long Tail Theory was eventually debunked, most notably by Anita Elberse, a professor at Harvard Business School.

Her research revealed that sales in the long tail simply didn’t behave as Anderson had predicted. Rather than bulking up and selling more, tails were becoming much longer and flatter and were actually generating fewer sales and profits—or nothing at all.

Some researchers believe the paradox of choice can overload customers with too many options, resulting in confusion and frustration. This may explain why infinite long tail products don’t sell.

However, Elberse found that blockbusters overwhelmingly reigned supreme in a variety of different industries. This included music (superstar artists on major labels), movies (Hollywood blockbusters), books (bestsellers), television (original programming), sports (star players), pharmaceuticals (blockbuster drugs), consumer electronics (Apple’s hardware), hospitality (Las Vegas strip hotels), and fashion (Burberry’s trench coat).

More importantly, her research proved what most retailers have known all along about the most popular, best-selling products:

“Our research showed that success is concentrated in ever fewer best-selling titles at the head of the distribution curve… an increase in concentration that is common in winner-take-all markets. The importance of individual best sellers is not diminishing over time. It is growing.”

In addition to Elberse, Wharton Professors have also debunked The Long Tail Theory, as have various other researchers and economists.

Yet, even faced with an abundance of empirical evidence, many pundits (and SaaS providers) still cling to The Long Tail Theory and incorrectly point to Amazon as proof that the strategy works. However, this view stems from a misunderstanding of how Amazon’s legendary flywheel actually works.

[toc-embed headline=”What About Amazon?”]

What About Amazon?

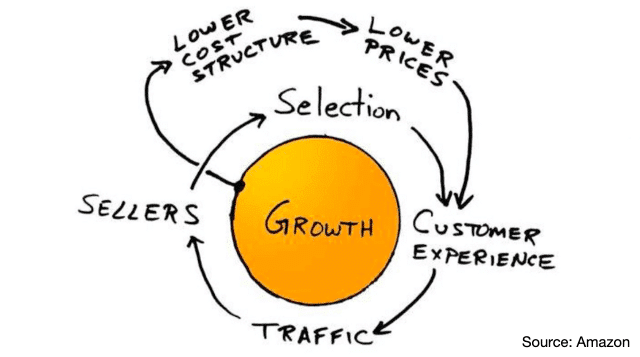

Known for offering Earth’s Widest Selection, Amazon boasts over a billion SKUs and generates billions in profits annually. Surely their marketplace and long tail strategy must be the key to their success.

But having spent 7+ years building retail businesses and reverse logistics at Amazon, I think it’s important to clarify that the company is not a retailer at all. It’s a data, technology, logistics, service, and media company that enables commerce in all of its forms.

Furthermore, its strategy is less about making incremental sales and profits in the long tail and more about relentlessly improving the customer experience by feeding its flywheel. To accomplish this goal, the company acts as a gatekeeper that grants access to its platform (with 300 million active users) and charges sellers progressively higher fees for using it. For every $100 in sales generated by sellers on its marketplace, Amazon now takes about $34 in fees, the bulk of which comes from fulfillment (FBA), referrals, and advertising.

Emulating Amazon is virtually impossible

To be clear, the motivation behind increasing product assortment in Amazon’s marketplace is not to capture incremental revenue and profits from the long tail. The financial benefits come from charging ever higher tolls, which it reinvests into its flywheel to strengthen its durable competitive advantages.

Since 2018, Amazon has spent $162 billion on CAPEX to widen its impenetrable moat. Unless a retailer is prepared to match CAPEX, it will never come close to offering the same level of services. Just ask Shopify or Google. Only JD.com and Alibaba’s Taobao and Tmall are seen as comparable businesses, while eBay has been left in the dust.

Of course, in the rare instances that niche products sold by third-party sellers transform into blockbusters, Amazon either buys the products and sells them for itself, or it copies the products and sells them under a private label. My team launched AmazonBasics back in 2009, but the company has since launched dozens of other private labels to compete in the most profitable niche and mainstream categories.

Yet even with its controversial private labels business, it’s been reported that Amazon is shrinking its selection to focus on bestselling goods instead of tens of thousands of items that sell in low quantities. In other words, it’s cutting the long tail short but continuing to invest in the highly-lucrative head, where all the bestsellers, hits, and blockbusters reside.

However, beyond the dream of profits in the long tail and the desire to copy Amazon, there was still one secret “perk” that gave third-party marketplaces a huge advantage over other retailers. This loophole allowed marketplaces to legally undercut the competition, which triggered a long, drawn-out war over the collection of state sales taxes.

[toc-embed headline=”Loophole Closed: Why Amazon’s Tax Nexus Advantage No Longer Exists”]

Loophole Closed: Why Amazon’s Tax Nexus Advantage No Longer Exists

Perhaps the most lucrative feature of marketplaces that no longer exists is sales tax loopholes.

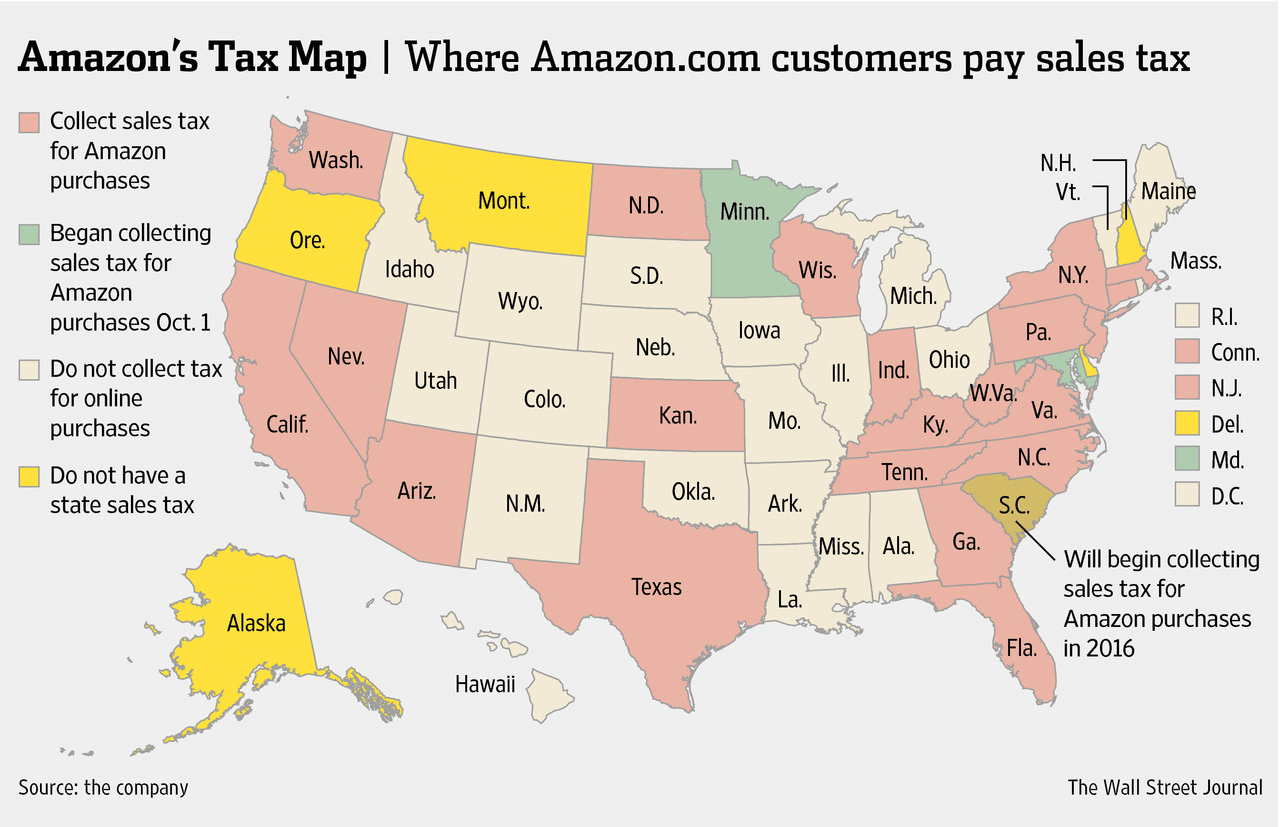

In the past, third-party marketplaces were extremely attractive business models because of tax loopholes that were exploited by Amazon and others. Legally, online retailers were not required to charge state and local sales taxes on purchases—as long as they didn’t maintain a physical presence or business connection (aka “nexus”) in the states where the transactions took place.

For years, online retailers argued that while they sold products all across the country, they didn’t have nexuses to the majority of the states and therefore were not legally obligated to charge sales taxes for them. Back in 2012, Amazon only collected sales taxes from five U.S. states where they had distribution centers and other operations. In 2014, that figure reached 20 states:

[Source]

Shoppers also didn’t pay sales taxes when they purchased products from a marketplace’s third-party sellers. Amazon argued that third-party merchants were responsible for handling their own tax collection and that collecting sales taxes would be administratively burdensome to take on.

Eliminating an unfair advantage

By undercutting rivals on prices, these loopholes gave Amazon and other marketplaces a massive advantage over brick-and-mortar retailers. But after mounting political pressure, many U.S. states eventually passed laws that compelled e-commerce retailers to collect sales taxes from their customers.

In March 2017, the days of shopping tax-free with Amazon came to an end when the company began collecting taxes everywhere. Later that year, Amazon introduced the Marketplace Tax Collection service to collect and remit sales taxes on behalf of third-party sellers as well.

Officially, the sales tax loophole was closed in 2018 after the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in the landmark case of South Dakota v. Wayfair, Inc. The court ruled that states may charge sales taxes on out-of-state purchases even if the seller doesn’t have a physical presence in the taxing state.

[toc-embed headline=”The Case for Dropshipping and a First-Party Marketplace”]

The Case for Dropshipping and a First-Party Marketplace

“I don’t think that small retailers should manage third-party marketplaces themselves. This is hard stuff—trust and safety processes, integrations, logistics, and shipping.

For most companies, I think dropshipping is a better path. The goal of a great marketplace is achieved. A retailer can own the customer experience, access great supply, and ensure excellent outcomes, while the merchant does the fulfillment.”

Todd Lutwak, Marketplace Expert, Former Board Partner at A16Z and VP of Selling at eBay

To summarize, the Long Tail Theory is debunked, Amazon’s business model can’t be copied, and sales tax loopholes are closed. Thus, there are no clear advantages to building and launching a third-party marketplace to expand product assortment and reduce inventory risk.

To succeed with a 3P marketplace, a retailer should focus less on offering an infinite long tail and more on building a highly-curated, carefully-organized, and rich product assortment that deeply satisfies customers in the head—where the vast majority of revenues and profits are.

But any retailer with a brand ethos that has spent years cultivating its image, differentiating its business, and building trust with its customers should be very cautious about ceding control to third-party sellers. There is no amount of “seller vetting” that can guarantee brand alignment, or completely eliminate operational or reputational risks.

With that being said, many of the benefits of 3P marketplaces can be achieved using dropshipping, which is a fulfillment model that allows retailers to sell products without keeping inventory in stock. Products are shipped directly from the vendor to the consumer, but most importantly, retailers retain full control over pricing, customer experience, and brand image.

With modern dropshipping software solutions, retailers can build a powerful first-party marketplace. They can quickly and easily connect with dropshipping vendors around the world, offer “extended aisles” of highly-curated products, and shift to an on-demand inventory model. Compared with a third-party marketplace, a dropship model is by far the superior option for retailers that have painstakingly built their brands and reputations over time.

Board of Directors @ fabric. Previously @ Google, Amazon, Staples, eBay, and Groupon.