Creating an Enterprise E-Commerce Business Strategy

E-commerce spending increased by 32.4% in 2020. Such growth represents an alluring opportunity for enterprises that haven’t yet entered—or perfected their entry—into the e-commerce space.

Though e-commerce giants like Amazon and Alibaba seemingly dominate online sales, there are still plenty of opportunities for enterprises to capitalize on online retail. Equally important is the ability of e-commerce to help enterprises weather a changing global landscape, especially one still reeling from the aftermath of COVID-19.

However, some enterprises—particularly small and medium enterprises—may find it difficult to access and adopt e-commerce technologies. Changes to existing workflows and processes may also be challenging to implement in the pursuit of pivoting to e-commerce.

Adopting a well-planned and versatile e-commerce strategy is critical for enterprises serious about taking advantage of e-commerce. E-commerce strategies let enterprises avoid many of the potential pitfalls that can lead to failure, but doing so requires full buy-in and support from the highest echelons of the company, including the C-level and board.

Developing, implementing, and sticking to an e-commerce strategy plan provides the necessary framework for an enterprise to enter the e-commerce space without over-extending itself or making critical and costly errors.

[toc-embed headline=”Step 1: Provide Consistent and Long-Term Support”]

Step 1: Provide Consistent and Long-Term Support

E-commerce business strategies define how an enterprise approaches and implements its e-commerce functionality. As such, an e-commerce strategy requires consistent and ongoing support on an organizational level—from the top-down, and at every step of the way.

E-commerce is not a project, rather a long-term investment in your brand, customer experience, and service levels. Albert Baladi, president, and CEO of Beam Suntory, which owns spirits brands such as Jim Beam and Maker’s Mark, agrees with this outlook for developing an e-commerce strategy that requires organization-wide support.

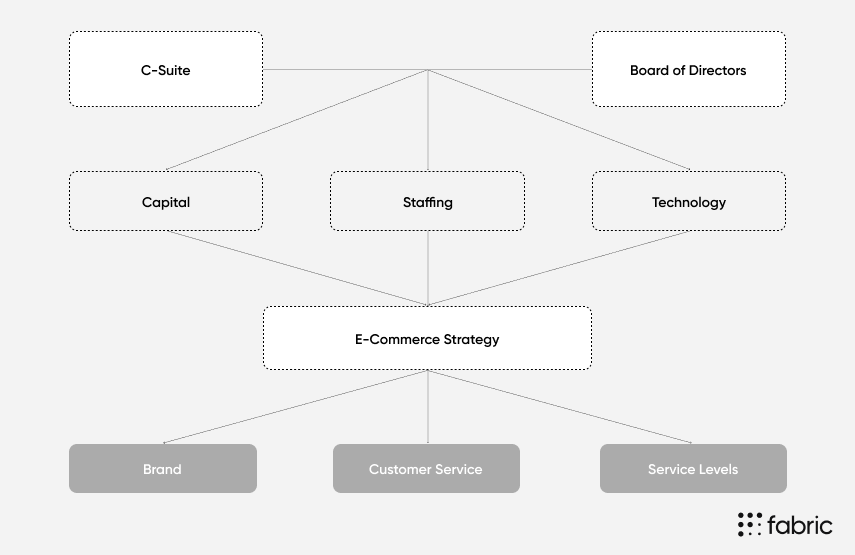

Support for e-commerce across the organization requires full-scale digital transformation, including:

- Changes to an organization’s structure

- Optimization of technology used

- Channel expansion

- A different approach to marketing and the customer experience

As a result, successful implementation of an e-commerce strategy may require significant changes in funding, including those that prompt objections from investors and other stakeholders, as was the case with Walmart’s pivot to e-commerce. In other words, an organization’s leadership must commit to providing resources when and where they’re needed while defending the long-term e-commerce business strategy versus the desire for short-term gains.

An illustration of the investments corporate leadership must make to adopt and implement a viable e-commerce strategy.

[toc-embed headline=”Step 2: Choose and Nurture the Right People”]

Step 2: Choose and Nurture the Right People

Implementing an e-commerce strategy plan requires a team—and leadership—that understands the e-commerce landscape and how to achieve the company’s goals. Simply repurposing people from other roles and trying to make them digital leads rarely works.

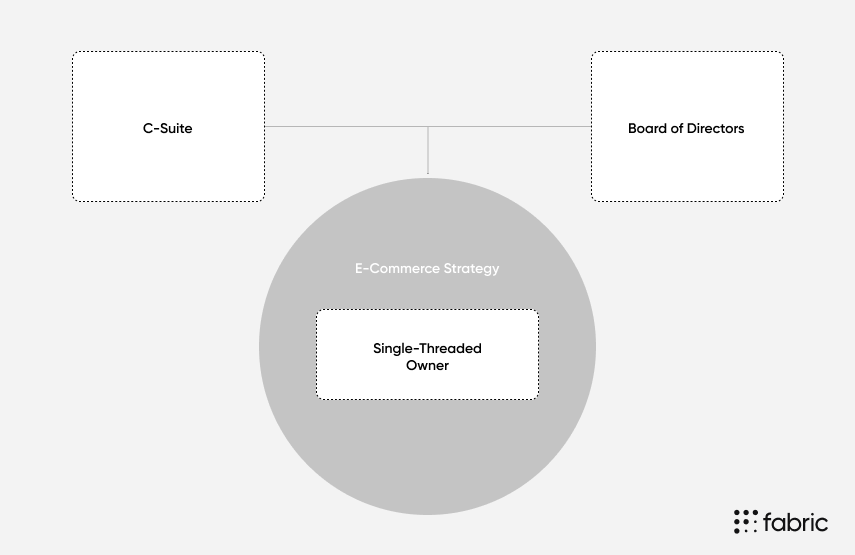

Enterprises must create and empower a skilled, versatile team to oversee their e-commerce strategy. Company leadership should delegate oversight of its e-commerce strategy to a single-threaded owner (STO) who can act with full autonomy to see the initiative through to completion. The STO should have the skills and confidence to lead and own the e-commerce business strategy, without other responsibilities necessitating that he or she multitasks.

Additionally, organizations need to hire for experience or look internally to “connect talent with opportunities.” This can be accomplished by shifting employees with experience and knowledge from one project or department to the most critical, highest-value role—but only if they fit the needs of the e-commerce strategy.

An organization’s executives and board of directors must delegate the company’s e-commerce strategy to an empowered and autonomous STO whose sole responsibility is implementing the strategy through completion.

[toc-embed headline=”Step 3: Develop a Tech Team”]

Step 3: Develop a Tech Team

Enterprises may outsource to system integrator (SI) firms for sourcing, deploying, and maintaining the architecture and tech stack required by an e-commerce business strategy. However, you must find an SI with a portfolio of work and skills that aligns with your goals. Also, finding an SI that prioritizes results over billable hours is critical for success.

Some organizations may benefit by choosing a fully in-house team over an SI, particularly if company leadership is open and responsive to tech changes and innovations. Under such an arrangement, a CIO (who may or may not also be the STO) may reject choosing monolithic e-commerce software in favor of a scalable, service-oriented solution.

As a result, the tech stack could be handled fully in-house to avoid the questionable goals of an outsourced SI or the likelihood of costly and time-consuming replatforming in the future.

[toc-embed headline=”Step 4: Keep Tech Simple”]

Step 4: Keep Tech Simple

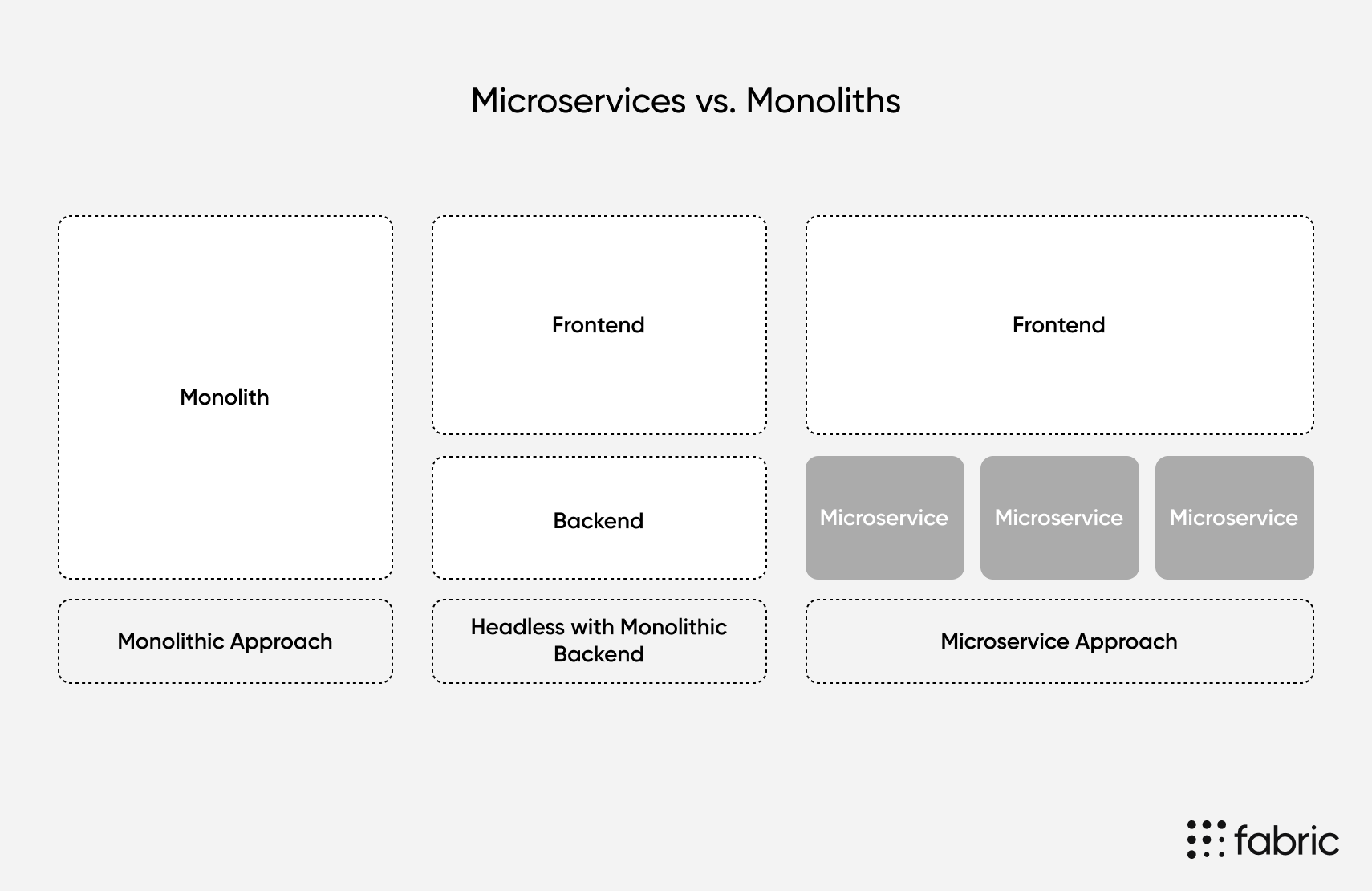

E-commerce websites are made of two components: the frontend and the backend. The frontend is the digital storefront and how customers interact with the brand’s website. It’s how customers search for products, add products to their cart, and checkout. The backend is where assets, content, and data are stored, which can also help brands unify the customer experience if they sell over multiple channels.

Complex tech solutions incur technical debt

When developing e-commerce strategies, enterprises may choose a monolithic platform like Oracle or Magento as the basis of their e-commerce store. Choosing a rigid e-commerce platform like this may seem like a safe choice, but it actually accumulates technical debt because the frontend and backend are so tightly interwoven.

As a brand’s e-commerce store grows, so, too, does its needs. In many cases, a simple fix may not exist for the brand’s platform of choice, necessitating costly and time-consuming development. In other situations, existing technology may make for a clunky customer experience that’s difficult for an enterprise to overcome.

A complex web of proprietary and monolithic retail software options can increase the total cost of ownership (TCO) of an enterprise’s e-commerce solution. To avoid “spending time-solving for edge cases [that] won’t change the quarterly results,” Bartley suggests enterprises “keep it [tech] simple.”

Monolithic vs. headless e-commerce

Three different approaches to implementing an e-commerce strategy. On the left, an example of monolithic platforms, which offer little room to iterate and necessitate resources and time to develop custom workarounds and solutions. In the center, an example of a headless frontend powered by a monolithic backend, which may still constrain the development of an omnichannel approach. On the right, a fully headless e-commerce architecture that lets enterprises scale by seamlessly deploying additional microservices as needed.

When developing an e-commerce strategy plan, care should be taken to choose a tech stack that will grow and scale as needed. Headless e-commerce architecture lets enterprises scale their e-commerce strategy via API-based microservices, like fabric OMS or fabric PIM, and a headless CMS and experience manager, like fabric XM.

Naturally, such microservices don’t need to be deployed all at once. Though an enterprise may not have an initial need for a loyalty management system, headless commerce lets the company implement it as needed when the time comes to grow and scale—without requiring significant development time or effort or incurring technical debt.

[toc-embed headline=”Step 5: Launch Fast, Iterate Later”]

Step 5: Launch Fast, Iterate Later

McKinsey claims that new e-commerce businesses can launch within four months. More complete launches can take between six and nine months, depending on an enterprise’s e-commerce strategy, approach, and partnerships.

McKinsey also cites a case study in which a brand launched a fully-functioning e-commerce store in only 13 weeks. Surprisingly, the store achieved nearly 3% revenue growth within its target market in just the first month of going live. In addition to deploying expert teams under leadership that owned the initiative, the brand realized its success by limiting the scope of its e-commerce strategy in an attempt to launch something quick, with future intentions of scaling as needed.

With a mix of headless and modular commerce, brands can launch early with a handful of customers. Like the example cited by McKinsey, an e-commerce strategy that calls for headless and modular commerce lets an enterprise release with all the functionality it needs initially, as well as the framework and architecture to continually iterate and scale in the future without incurring technical debt.

[toc-embed headline=”Step 6: Nail the Basics”]

Step 6: Nail the Basics

Launching an e-commerce site quickly means foregoing complex functionality that’s not immediately necessary. To do so, Bartley recommends e-commerce business strategies that prioritize:

- Site speed

- A simple layout and feature set

- Avoidance of “shiny objects” like personalization (at least initially)

- Letting the team focus on features that return results before implementing new ones

Headless products like fabric Storefront let enterprises launch simple, yet customizable e-commerce stores within a day. And because Storefront uses headless architecture, additional functionality can be added as demand calls for it. Once the store’s up and running, workflows have been optimized, and processes are functioning as expected, features like personalization and promotions can be seamlessly implemented without significant development time.

[toc-embed headline=”Step 7: Measure Input Goals”]

Step 7: Measure Input Goals

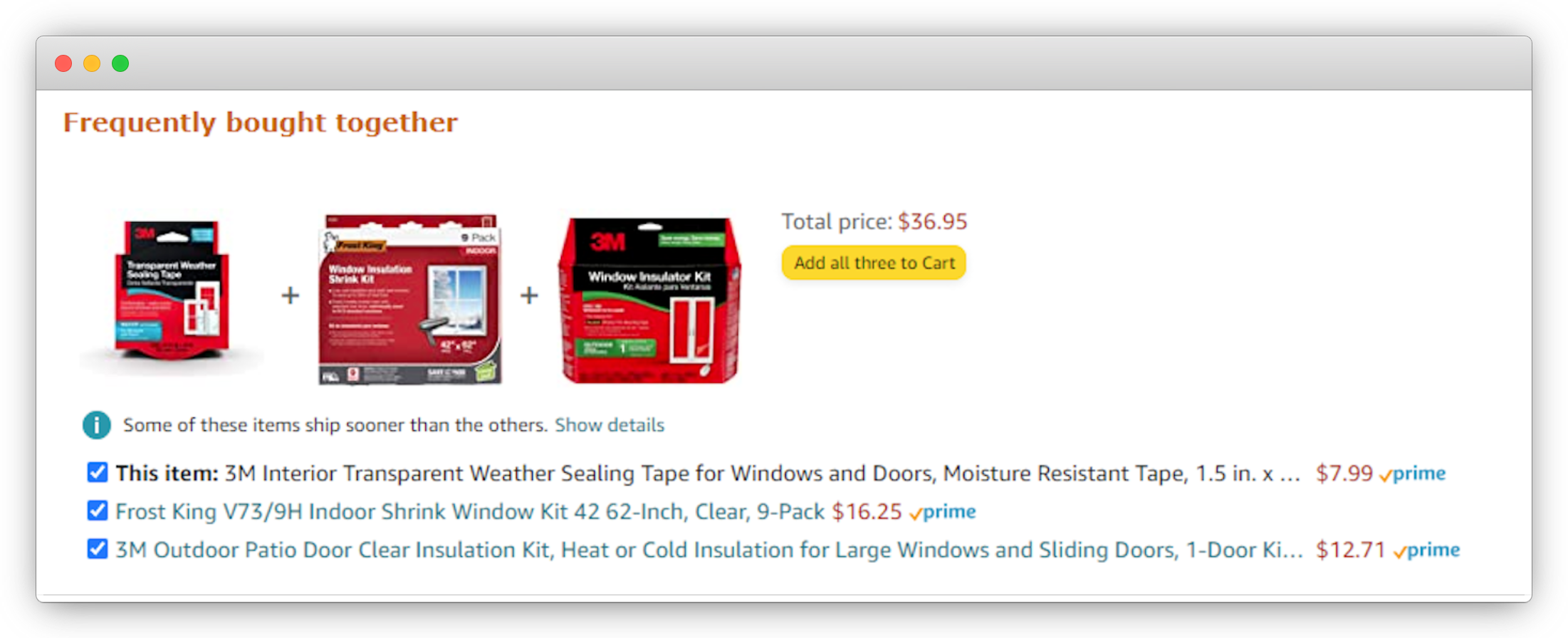

A tech team focused on increasing customer purchases (the input goal) could implement “Frequently Bought Together” functionality—as Amazon has—leading to 45% more clicks and, potentially, higher sales (the output goal).

Businesses often (and rightfully) track and measure output goals to determine the performance and success of an initiative. As part of an e-commerce strategy, output goals may include metrics like revenue, growth, and market share.

However, output goals aren’t easily controlled. Instead, STOs and their teams should focus on—and measure—input goals. Input goals, which have long been touted by Amazon, are tasks that are directly actionable and controlled—tangible actions a team can take and easily tie to performance metrics.

An e-commerce strategy should lay out what input goals are measured and how the team can directly impact them. For example, how can the team improve the add-to-cart conversion rate? If the rate is lower than expected (the average cart abandonment rate is 69.8%), what changes can the team implement to improve conversions?

By focusing on input goals as part of an e-commerce strategy, enterprises can more directly influence their output goals. For example, making the checkout experience more convenient (the input) directly correlates to fewer cart abandonments that, in turn, improve sales and revenue (the output).

[toc-embed headline=”Key Takeaways”]

Key Takeaways

- An enterprise e-commerce strategy begins with consistent and long-term support from the top down, including delegating the initiative to a single-threaded owner solely responsible for managing it.

- Key components of enterprise business strategies should include guidance on hiring and developing a skilled team, plans for a tech stack that’s simple to implement but easy to scale, and input-oriented goals vs. output metrics.

- An e-commerce strategy that prioritizes headless solutions lets enterprises launch quickly and continually build, iterate, and scale over time without incurring technical debt.

- Embracing headless architecture, like fabric XM, helps enterprises meet their e-commerce strategy goals.

Tech advocate and writer @ fabric.