The Hidden Cost of Capital Misallocation in Tech

This article was originally published on LinkedIn.

For an industry chock-full of smart and talented people, there is a tremendous amount of unintelligent capital allocation that takes place in the technology sector. Microsoft’s doomed acquisition of Nokia, the spectacular collapse of Quibi, and numerous dot-com flops have led to permanent losses of capital for shareholders over the years.

Last December, I wrote about the e-commerce duel between Amazon and Google and how Google’s latest efforts likely won’t succeed amidst fierce competition from online retailers. After wasting two decades trying to build a viable e-commerce business to compete with Amazon, the search giant ultimately ended up right back where it started, all while racking up billions of dollars in financial losses and opportunity costs along the way.

Meta is no different. The social media company’s first generation of online stores failed, and its second attempt didn’t fare much better.

It took nearly ten years and a third major push to start offering native shopping and checkout within the Instagram and Facebook apps. Yet even today, Meta has done little to combat scams or address complaints, which has further eroded the trust of its customers and merchants.

Amazon, on the other hand, has set the standard for expanding into fertile new markets and building ideas into massive businesses.

The company has a long history of doubling down on its most promising opportunities, which allowed my former teams to launch businesses such as AmazonBasics, Amazon Warehouse, Amazon BuyBack, and Amazon TradeIn, to name a few.

Over the years, this approach enhanced Amazon’s core e-commerce operations and allowed the company to branch out to create powerful new revenue streams. For example, 1-Click ordering became a runaway success, with the patent once holding an estimated value of $2.4 billion. Amazon Business recently ballooned into a $25 billion a year business, Amazon Web Services (AWS) now generates $71 billion per year, Amazon’s advertising business adds $31 billion per year, and Amazon Prime and other subscriptions bring in $31.8 billion per year.

Then there’s the $107.69 billion it generates from third-party marketplace sellers. In addition to booming commissions on sales and fees from Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA), revenue will now get juiced even more by the newly launched ‘Buy with Prime.’ This service will allow third-party retailers to use its vast Prime delivery network to fulfill orders on their own websites (which also places soul-crushing pressure on Shopify Fulfillment Network and its recent Deliverr acquisition).

When you break it all down, each one of Amazon’s business divisions can be a huge standalone company. Combined together, they make the online retail colossus seem practically invincible.

For the three months ended March 31, 2022, the company generated $116.4 billion in revenue, up from $108.5 billion a year ago.

Amazon’s Kryptonite

However, Amazon’s armor is not impenetrable. Capital allocation is the process of determining the most efficient investment strategy for an organization’s financial resources, with the goal of maximizing shareholder equity.

When it comes to acquisitions, Amazon has struggled while Google has excelled at identifying and buying attractive takeover targets with potential for extraordinary growth. The company’s history of success proves that Google—not Amazon—has been blessed with the uncanny ability to turn at least some of what it touches into gold.

[toc-embed headline=”The Midas Touch of Tech”]

The Midas Touch of Tech

Where Google shines brightest is with its ability to acquire exciting startups with blockbuster potential. In an industry where you only need one strong acquisition to catapult your company to the stratosphere, Google has had several wildly successful ones.

- Applied Semantics: a semantic text processing technology company bought for $102 million in 2003. It gave birth to AdSense, which generated over $15 billion in revenue and represented 23% of the total revenue for Google in 2019.

- Android: the mobile operating system was acquired for $50 million in 2005. Today, it has a 70% market share of the global mobile operating system market versus 28% for Apple’s iOS.

- YouTube: the video streaming platform purchased for $1.6 billion in 2006. It generated $28.8 billion in ad revenue last year and is the second most visited website on the planet, trailing only Google.com.

- DoubleClick: the advertising company bought for $3.1 billion in 2007. It gave Google a foothold in the display-advertising industry and has built its ad-buying business from the ground up.

These acquisitions have fueled the company’s growth over the years. For the three months ended March 31, 2022, Google generated $68 billion in revenue, up from $55.3 billion a year ago.

More recently, Microsoft has taken up the mantle from Google. Between LinkedIn, Nuance, Minecraft, GitHub, ZeniMax, and Activision Blizzard, CEO Satya Nadella may have put together the most impressive win streak in M&A of this generation.

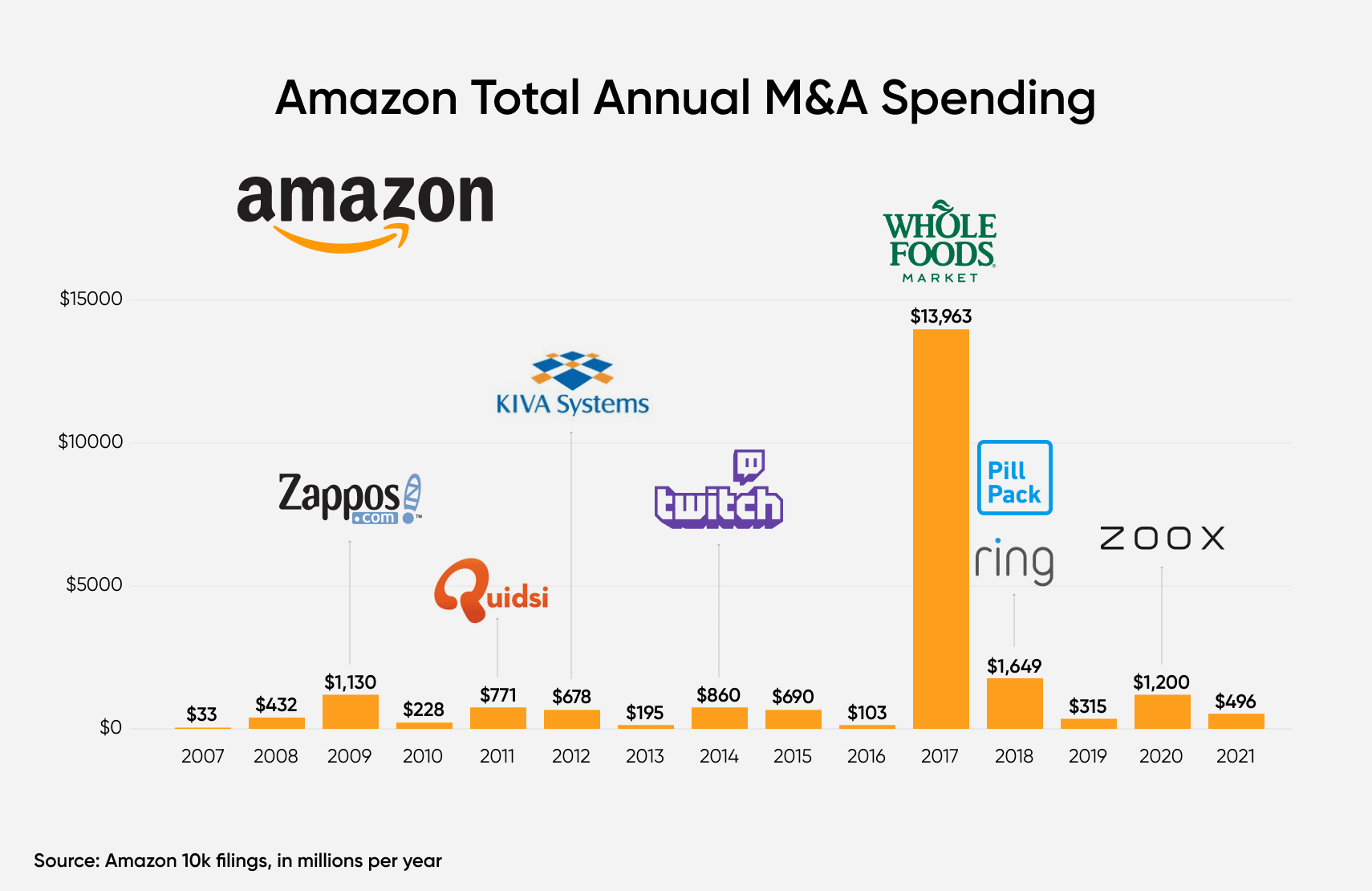

In contrast, Amazon’s track record leaves much to be desired. Although the e-commerce giant spent billions on splashy acquisitions over the years, some turned out to be problematic deals that likely should’ve been avoided.

So what went wrong? How can a company like Amazon, with a reputation for brilliance in one area of capital allocation, be so deficient in another?

First, it helps to understand that while these tech titans compete in certain areas, the differences in their business models require very different capital allocation strategies. Google is an attention merchant that generates the vast majority of its revenue from ads, Microsoft is a software company that focuses on productivity and business, cloud, and personal computing, and Amazon is gradually moving beyond retail to become a services company through AWS, subscriptions, fulfillment, and advertising.

Second, it also helps to understand Amazon’s economics. Unlike other businesses in tech—or any industry for that matter—the company stands out as a highly unusual enterprise that must contend with a very unique problem.

[toc-embed headline=”Amazon’s Hidden Moat: A Negative Cash Conversion Cycle”]

Amazon’s Hidden Moat: A Negative Cash Conversion Cycle

“Because of our model, we are able to turn our inventory quickly and have a cash-generating operating cycle. On average, our high inventory velocity means we generally collect from consumers before our payments to suppliers come due.”

Amazon.com, Inc. (2021). Form 10-K. (p.18)

Much has been written about Amazon’s obsession with free cash flows, its hyper-efficient operations, and how it achieves what’s known in accounting as a negative cash conversion cycle (CCC).

Yet as someone who built Amazon’s inventory management systems for hardline products in the early days, I can tell you that there are few people who understand the importance of this competitive advantage or how it created the fuel that powered Amazon’s growth for over 27 years.

The CCC is a metric that tracks the number of days it takes for a business to convert inventory into cash.

But the holy grail of retail operations is a negative CCC because it means you sell inventory and collect payments from customers faster than it takes to pay your suppliers. In effect, suppliers end up financing your operations interest-free, which means the business requires zero capital to grow.

Amazon’s negative CCC is an extraordinary achievement surpassed by only one other company of comparable size and scale: Apple Inc. Keep in mind, Amazon’s mastery of supply chain management is rated on par with Apple, even though it boasts Earth’s Widest Selection and sells over a billion SKUs.

The secret weapon buried in Amazon’s balance sheet

What most people don’t realize is that achieving a negative CCC does more than just free up money that would otherwise sit in inventory. It can free a balance sheet from short-term loans, financing, or factoring that many companies use to boost working capital.

More importantly, it also weaponizes Amazon’s growing hoard of cash. Until it pays its suppliers, all the money it generates turns into interest-free rocket fuel that gives the company the optionality of doing a variety of things, including buying short-term paper or re-investing in the business to accelerate growth.

This collect-now, pay-later business model bears a resemblance to insurance, subscription services, gift cards, loyalty programs, and other businesses that generate streams of interest-free cash (sometimes referred to as “float”). It’s what allowed a business like Amazon—historically a barely profitable business with low margins and low returns on invested capital (ROIC)—to grow its assets at a CAGR of 50% over the last 27 years.

How much “float” does Amazon actually carry?

Because of its negative CCC, balance sheet items like accrued expenses and unearned revenues (which include upfront payments for Prime memberships and AWS) can be treated like temporary cash balances instead of current liabilities. Combine this “float” with existing cash and marketable securities, and we get an estimate of the amount of money Amazon holds on its balance sheet at any given time.

At the end of 2021, this figure reached a staggering $159.7 billion. That’s up $21.5 billion from the year before and up $115.2 billion from 2016.

[toc-embed headline=”Amazon’s $160 Billion Problem”]

Amazon’s $160 Billion Problem

With unfettered access to free capital, Amazon can afford to experiment and fail. Even so, attempting to allocate increasing amounts of capital towards a finite number of attractive opportunities is not easy.

For the first time in a decade, Amazon repurchased $1.3 billion worth of shares in early 2022 and then recently announced another $10 billion worth of share repurchases as well. Buybacks can increase shareholder value but don’t actually generate returns for the company.

Amazon also happens to be a very capital-intensive business that carries some of the highest depreciation expenses in corporate America. Depreciation hit $34.3 billion last year, which means the company needed to spend at least that amount on repairing and replacing aging plants and equipment to maintain the health of the business.

It poured $61 billion into capital expenditures in 2021.

In fact, CAPEX skyrocketed to $101.2 billion over the last two years, which is $28.8 billion more than all previous years combined.

Yet, even with these huge capital outlays, Amazon still struggles with deploying its growing cash hoard. What happens when a company exhausts most of its options but still needs to find ways to put its capital to work?

If you’re Amazon, you throw money at acquisitions and investments.

In the midst of growing antitrust scrutiny, Amazon recently acquired MGM and is making a push into the transportation sector with its purchase of Zoox and deals with Rivian, Aurora, and Stellantis. But with the Rivian stake alone, Amazon just took a $7.6 billion loss last quarter. And with the jury still out on if these other deals will pay off, it helps to revisit some of its past acquisitions to see how they fared after being bought by Amazon.

[toc-embed headline=”The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly”]

The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly

With the exception of AWS, which is a smash hit made up of over a dozen acquisitions, many of the companies Amazon purchased over the years haven’t flourished into the disruptive powerhouses they were promised to be.

Some examples of reasonably good acquisitions that Amazon prioritized for market leadership include video game streaming platform Twitch, online pharmacy PillPack, home security and smart home company Ring, and fulfillment robotics company Kiva Systems (renamed Amazon Robotics).

But those are the rare highlights out of the estimated 111 deals Amazon completed through 2021. Splashy acquisitions like LivingSocial, Woot, Drugstore.com, Fabric.com, Joyo.com, and Quidsi (parent of Diapers.com) were questionable purchases that never lived up to the hype, while massive deals like Whole Foods and Zappos were some of the most expensive and disappointing acquisitions that Amazon ever completed.

Big losses at Whole Foods

Sales for Amazon’s physical stores have been dismally flat since Amazon purchased Whole Foods back in 2017 for $13.7 billion. Since the acquisition, the company has failed to disrupt the $800 billion grocery segment despite building 25 Amazon Fresh locations and opening 30 additional Whole Foods locations (going from 470 to 500).

Increased competition in organic foods and grocery delivery, lack of an independent online presence, poor execution of plans to improve operations, and the rapid deterioration of the in-store experience have all contributed to the company’s underperformance over the last few years.

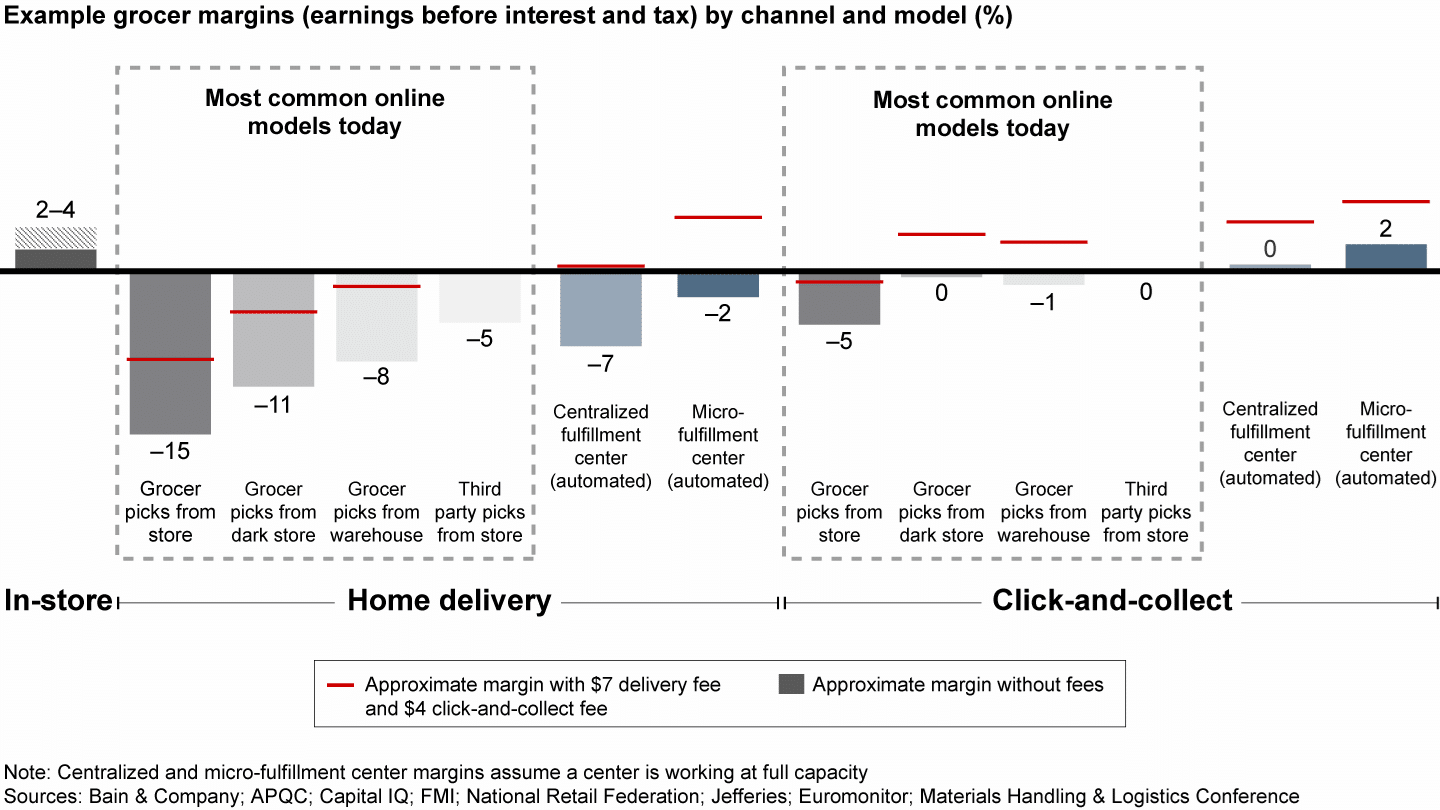

What about online sales? The opening of “dark stores” and investments in e-commerce have boosted online ordering, but these models have likely incurred heavy losses. Even the launch of a controversial $9.95 delivery fee may not be enough to stop the bleeding. The chart below shows how difficult it is for grocers to earn a profit with home delivery and click-and-collect models.

Clearly, the “Amazonification” of Whole Foods hasn’t worked. Its poor performance recently triggered a slew of organizational changes to consolidate operations. But with growing losses and a deteriorating core business, this acquisition has not been the game-changer that Amazon originally envisioned.

Zappos: Next on the chopping block?

Amazon purchased online shoe retailer Zappos for $1.2 billion back in 2009. But although the business consistently ranked high for customer service, people predicted for years that Zappos would get shut down because of slowing website traffic and diminishing sales.

According to a new book by Wall Street Journal reporters Kirsten Grind and Katherine Sayre, Amazon executives wanted Zappos to meet a series of goals in 2020 and 2021 because the business was only hitting about 30% of its profit targets with no clear plans to improve its operations.

Compounding the problems was Nike’s decision to drop the company as a wholesale partner in August 2020. Meanwhile, Amazon became the top retailer for US apparel and footwear when it surpassed Walmart in 2020.

With slowing sales and nothing more to teach Amazon, it’s become clear that Zappos has outlasted its usefulness as an independent subsidiary of the parent company. Considering Zappos’ culture and checkered past, it may be time for Amazon to finally lay the company to rest.

[toc-embed headline=”Amazon’s Build vs. Buy Culture: Allocating Capital to Future Growth Engines”]

Amazon’s Build vs. Buy Culture: Allocating Capital to Future Growth Engines

Without a doubt, Amazon is a benchmark against which many other tech firms measure themselves. Jeff Bezos and his team built a business with an extremely wide moat that has expanded well beyond its initial core competencies.

But while the company has made great strides in building successful businesses, it hasn’t quite found the same transformational success with M&A. Its track record for buying companies pales in comparison to Google, which has laid claim to multiple blockbuster acquisitions over its storied history.

Amazon’s inability to find and acquire truly game-changing businesses is perhaps one of the only major weaknesses in the company’s impregnable armor. Therefore, I don’t expect its latest buying spree to amount to much.

The MGM deal may provide a boost to Prime memberships, but the future growth engines will likely be financial services, transportation and logistics, business and cloud services, and advertising—opportunities where Amazon can deploy vast amounts of capital to strengthen its competitive advantages, grow its business, and ultimately increase its shareholder value.

Jeff Bezos once told his employees that “one day Amazon will fail” and that it is their job to try and delay that day for as long as possible. Disappointing quarterly results are bound to happen from time to time, but if the company can narrow its focus and continue building on its strengths, it may be able to push that day out farther than the eye can see.

Board of Directors @ fabric. Previously @ Google, Amazon, Staples, eBay, and Groupon.