Meta’s Shrinking Moat and Their Failure to Deliver Social Commerce

Up until recently, no one could’ve predicted the economic decline of one of the most powerful advertising juggernauts this world has ever known. Boasting a superior business model that required minimal capital expenditures (CAPEX) to run, Meta (then known as Facebook) previously looked unstoppable as it swallowed up Instagram and WhatsApp, funneled billions of free cash into infrastructure, and quickly became the dominant social media giant of its time.

But even back in 2010, Meta feared it would become a one-trick pony, which was why the company set its sights on the next big opportunity: social commerce.

By building a commerce infrastructure that would allow products to be bought and sold directly on its social media platforms, the company could completely redefine the e-commerce and advertising landscapes by creating a self-perpetuating virtuous circle:

i.e. Everybody would use Meta because every ad and product was on it, and every ad and product would be on it because everybody used Meta.

“If I had to guess, social commerce is the next area to really blow up.”

– Mark Zuckerberg, August 2010

At the time, the future looked very promising.

[toc-embed headline=”It’s 2023, Where’s Social Commerce?”]

It’s 2023, Where’s Social Commerce?

Years later, Meta Commerce has yet to “blow up”.

Sure, there’s Facebook Marketplace, which has found some success against Craigslist and eBay. Interestingly, the platform dominates e-commerce in Bangladesh, where Facebook is considered to be the default internet for millions of people. However, Facebook Marketplace remains a free peer-to-peer service that doesn’t drive much revenue and is limited to how much it can scale beyond the used goods market.

The ultimate prize has always been a slice of the $1.2 trillion social commerce market. Yet even with a teflon balance sheet, troves of user data, and no viable competitors against Facebook and Instagram for years, Meta repeatedly failed to capitalize on opportunities that should’ve been easy layups for the social media giant.

[toc-embed headline=”The Spectacular Failure of Meta Commerce”]

The Spectacular Failure of Meta Commerce

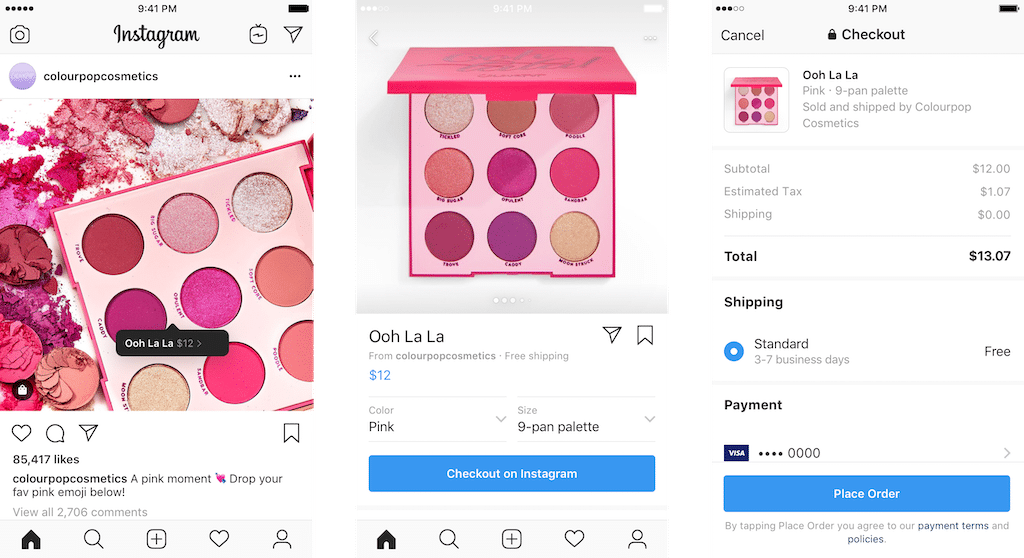

Over the years, some of Meta’s biggest duds were Facebook Commerce (aka F-Commerce), Facebook Gifts, and live shopping—past efforts that didn’t gain any real traction. Checkout on Instagram was launched to create a fast and native checkout experience within the app, but the feature was never extended beyond tagged products from a brand’s shopping post.

[Source]

In 2020, Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg finally turn made commerce a top priority within the organization.

To capture the e-commerce boom from the COVID-19 pandemic, he tasked 1,000 engineers with building out commerce features for Facebook and Instagram and later launched Shops to allow brands to set up online stores that could be accessed within its family of apps. He announced high-profile partnerships with Shopify, BigCommerce, and WooCommerce, and also rolled out Shopify’s checkout, Shop Pay, as an alternative to powerful buy buttons by PayPal and Apple Pay.

But less than two years in, reports began to surface that Meta Commerce was turning into a disaster.

A breakdown in leadership

Despite hiring talented leaders for the e-commerce initiative, Meta’s fervent rush to go to market produced disturbingly poor results. They built products and features that were crude and rudimentary, and then shipped those products to retailers, knowing full well they would be disappointed. According to the Wall Street Journal:

- Retailers had a hard time actually setting up their Instagram and Facebook Shops.

- Basic order and post-order management functionality were lacking. Integrations with other shopping platforms were superficial and lacked basic order tracking, fulfillment, and orchestration.

- Some of the most basic features for commerce were missing, such as the ability to offer items in different colors or sizes, limit where a merchant can ship items, provide next-day or same-day deliveries, and the ability to post numerous photos for different colors of a product’s availability.

- Key executives that were responsible for building out Meta’s commerce features had left the company.

Customer complaints soared, especially about post-transaction experiences. It’s been reported that many customers had no idea when products would arrive and would often receive the wrong items when they did. When customers tried to contact shops, the sellers were nowhere to be found.

250 million customers that bought nothing

In fact, not only did Meta fail to get the basics of an e-commerce platform right, but they made the crucial mistake of de-prioritizing the building of native commerce experiences within Facebook and Instagram Shops. They felt it would be easier to sign up retailers by allowing customers to complete their checkouts through brand websites instead of natively through Facebook and Instagram.

In Q1 2021, Meta announced that brand signups reached more than 1 million monthly active Shops and drove over 250 million monthly visitors to Shops.

What they didn’t reveal, however, was that customers never actually bought anything.

What was supposed to be the ultimate frictionless e-commerce destination, turned out to be a tragically bad shopping experience that nobody ever used. Hemorrhaging cash and generating dismal sales, Meta was forced to abandon many of its commerce plans altogether.

One by one, Meta’s failures began to pile up

In the months that followed, more reports began to surface about poorly built technology, internal strategy squabbles, poor sales, and a deepening crisis over Apple’s impact on its advertising revenue.

The much-hyped rollout of Shopify’s Shop Pay to all merchants did little to slow the train wreck, while the company backpedaled on a number of commerce initiatives. Some of the projects they scaled back included Meta’s investments in ‘creator commerce’ within Instagram shopping, its ‘Friends & Family Shopping’ section, community-driven shopping projects, and visual search.

[Source]

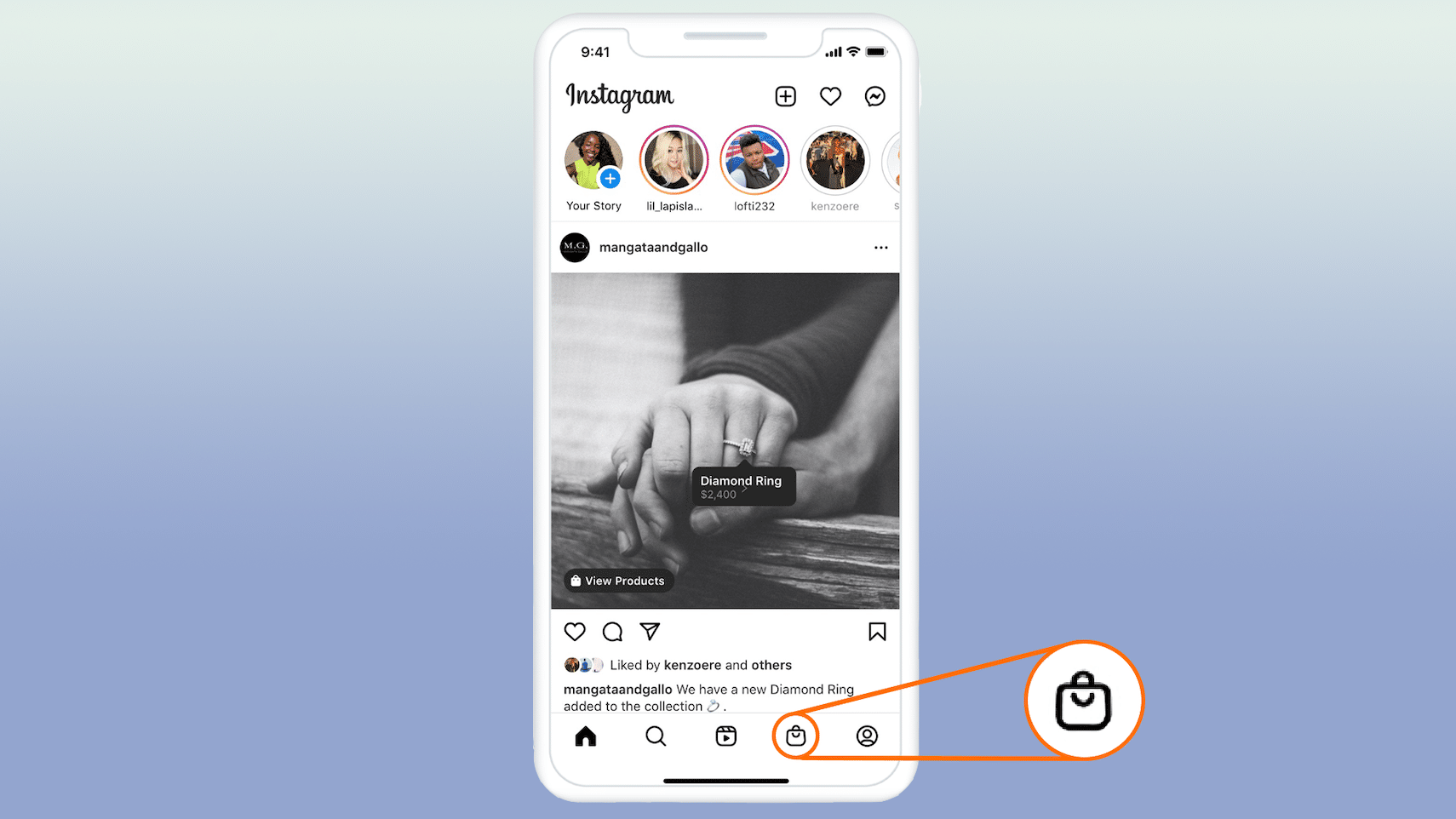

The “Shop” tab on Instagram was also a big flop. Meta’s leadership was convinced they could change user behavior by getting people to click a new button on its main navigation bar and shop for random items.

Turns out, brands saw increased traffic but generated no incremental sales due to the poor native shopping experience. The removal of the Shop tab is just the latest disappointment in a long string of misfires that have plagued the company’s latest e-commerce push.

[toc-embed headline=”Commerce 101: Where Meta Went Wrong”]

Commerce 101: Where Meta Went Wrong

The entire appeal of shopping on Instagram was the promise of an incredible native experience with highly relevant products surfacing in the vertical scroll of a user’s personal feed.

At a minimum, Meta needed to follow best practices with robust e-commerce capabilities for managing products, prices, promotions, inventory, orders, cart, and checkout. These basic commerce functions create the foundation for shopping experiences that feel familiar and consistent for customers.

But Meta not only failed at building basic commerce functions, they also neglected the post-checkout experience as well. For any commerce platform, post-checkout is just as important (or arguably more important) than just serving APIs that let you list, recommend, or pay for products.

This is a massive gap in how Meta has approached e-commerce.

But retail is logistics. As I’ve discussed previously, order tracking, fulfillment, returns management, and visibility into the first, middle, and last mile are highly difficult, yet critical logistics problems to solve. Efforts to engineer a shortcut like Shopify or attempt halfway measures like Google can only end badly as Amazon and others continue to invest in and strengthen these crucial commerce functions.

Now there’s an even bigger problem

In the past, Meta was free to aggressively raise prices on its ads, which caused ad rates to soar higher across its platforms. Today, its advertising rates are falling, reflecting a sudden loss of pricing power and the erosion of its durable competitive advantage.

According to media buying firm Anagram, Meta’s average cost per mille (CPM)—the cost advertisers pay to reach 1,000 people—decreased 4.5% compared to 2021. The agency also expected Meta’s Q4 2022 ad prices to decrease a staggering 23% year-over-year.

[toc-embed headline=”Tech Titans Are Devouring Meta’s Core Business”]

Tech Titans Are Devouring Meta’s Core Business

A moat describes a company’s competitive advantage or the barrier that protects a company’s market position from competitors. For years, Meta’s user base and wealth of consumer data ensured that Facebook and Instagram had no close substitutes, making their users highly attractive to advertisers.

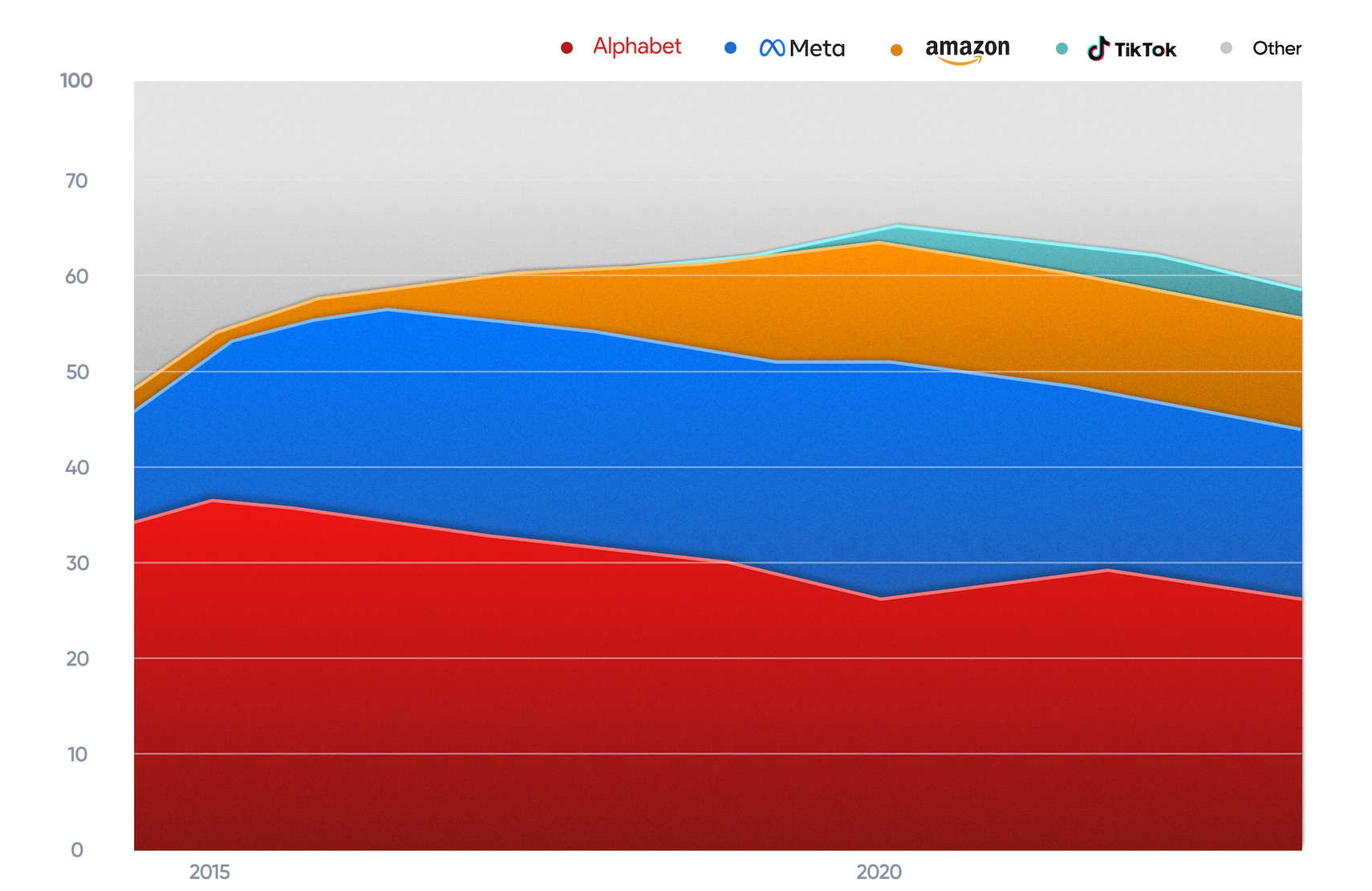

But radical changes in media economics have rapidly altered the digital landscape and upended traditional advertising models. With competition catching up, the once invincible duopoly of Google and Meta has now come under siege and is deteriorating faster than anyone could’ve imagined:

- Apple has aggressive plans to triple its $4 billion ad business after going thermonuclear on Meta with its iOS privacy changes. The move cost Meta $10 billion.

- Amazon has quietly built a fast-growing $31 billion ad behemoth, a business that triggered Google and stole ad budgets from Meta. Even slow and sleepy Walmart is coming in hot with a $2.1 billion ad business growing at 30% YOY.

- Microsoft is taking Google’s crown jewel head-on with the magical debut of OpenAI’s ChatGPT and its recent $10 billion investment in the startup. The new chatbot has reportedly set off a “Code Red” at Google.

- ByteDance’s TikTok has gobbled up a huge market share, with ad revenues doubling from the previous year to hit $10 billion in 2022.

[Source]

The one-two punch of Google and Meta has had a stranglehold on the online advertising business for years, controlling over 50% of total digital ad spend in the U.S. since 2014. But according to Insider Intelligence, they’ll capture just 48.4% of all U.S. digital ad revenue in 2022 (19.6% for Meta), down from 54.7% at their peak in 2017 (20.0% for Meta).

The blitzkrieg assault on Meta’s core business is not letting up

Investors may have cheered the company’s latest financial results, but a 38% decline in operating income is a huge red flag that should be scrutinized more closely. According to their latest earnings call, CFO Susan Li revealed that Meta’s operating margins, which historically averaged over 39% since the company went public, cratered to just 20% in Q4. Not surprisingly, commerce was dragging the business down:

“Growth remained negative in our largest verticals, online commerce and CPG, though the pace of year-over-year decline in online commerce has slowed compared to last quarter.”

The company also announced a giant $40 billion increase in its stock buyback program, which indicates that Meta’s opportunities to earn superior returns on invested capital (ROIC) are quickly disappearing.

[toc-embed headline=”It’s Still Not Too Late: Meta’s Golden Opportunity to Dominate Social Commerce”]

It’s Still Not Too Late: Meta’s Golden Opportunity to Dominate Social Commerce

Although the strength of Meta’s franchise has weakened, the massive opportunity to lead the pack in social commerce has not disappeared. The company still has a unique opportunity to sell brands and aspirational commerce, which is a notoriously difficult market that Amazon hasn’t been able to crack.

Tencent’s WeChat started off as a messaging app (similar to WhatsApp) but then morphed into a super app by adding many additional applications, including food delivery, grocery orders, ride-hailing, payments, e-commerce, and much more.

If Meta aspires to emulate WeChat by building the ultimate “super app”, commerce is arguably the most important piece of the puzzle that’s still missing. A frictionless native shopping experience with seamless payment, cart, and checkout capabilities could even be the engine that drives user engagement in the metaverse and allows Meta to finally monetize WhatsApp as well.

The dream of creating a self-perpetuating virtuous cycle is still within reach

But the window is closing fast.

TikTok understands this opportunity better than anyone and has wisely made social commerce part of its core business strategy. Powered by a true commerce platform complete with e-commerce primitives and APIs, its growing dominance not only poses an existential threat to Facebook and Instagram but also to Amazon and Google as well.

The Information reported that TikTok’s Chinese parent company, ByteDance, grew gross merchandise volume (GMV) in China by 76% to $206 billion in 2022. Meanwhile, TikTok’s e-commerce GMV in Southeast Asia more than quadrupled to $4.4 billion. If the app can avoid an outright ban, TikTok has plans to step up its e-commerce push in the U.S., Brazil, Spain, and Australia.

[toc-embed headline=”Expanding Meta’s Moat for the Long Term”]

Expanding Meta’s Moat for the Long Term

Meta’s core business is facing mounting challenges. Today, well-capitalized and motivated competitors offer better, more engaging user experiences than Facebook and Instagram. If the company doesn’t innovate itself out of this predicament, it’ll only be a matter of time before its user base crumbles and its lead in digital advertising disappears into thin air.

However, the metaverse alone will not be the silver bullet that Mark Zuckerberg envisions. Citi estimates that by 2030, the total addressable market (TAM) for the metaverse can reach $8 to $13 trillion. That’s a fraction of the $38.4 trillion TAM for the global digital economy (assuming it accounts for 30% of GDP). Furthermore, Meta’s massive CAPEX on the metaverse has yet to deliver any meaningful results.

While I applaud the vision to position Meta as the Android to Apple’s iOS, their plan to leapfrog Apple and free itself from the shackles of their app tracking transparency (ATT) crackdown feels more like a distraction rather than a sustainable long-term strategy.

To be clear, Meta has lost some—though far from all—of its franchise strength. Although it faces increased and intensified competition, Meta still has the tools, talent, and capital to seize an enormous opportunity that no other competitor has.

Commerce is intrinsically social and Meta is uniquely positioned to orchestrate highly aspirational customer experiences with its social media platforms. Facebook and Instagram have become ubiquitous in people’s lives and building a complete, holistic shopping experience that encompasses logistics and taps into the muscle memory of consumers will be critical if Meta wants to compete in the crowded e-commerce space.

More importantly, Facebook and Instagram still have massive captive audiences that are frequently inspired and want to shop for the brands they love in environments that are native to how they operate.

Why not give retailers and brands what they want?

If Meta can refocus its efforts on commerce, it could disrupt the digital landscape and use its learnings to fuel its metaverse ambitions. Let’s just hope they don’t waste two decades (like Google) trying to figure it out.

Board of Directors @ fabric. Previously @ Google, Amazon, Staples, eBay, and Groupon.